I should have written this letter years ago, not today after reading of your death in The New York Times. And though you will never read my words, I still need to write how much I learned from you and what’s more, how important it was for me that such a person as you existed. We never tell people how much just knowing that they’re alive means to us until it’s too late. Reading your poems I learned to look on the edge of things and not to be afraid of going out on a limb. You taught me that writing a poem is like hikng a mountain trail, never taking a direct ascent, but a series of switchbacks slanting sideways to the summit. Your language was simple and honest, never inflated like some puffed up toad. If I had to use one word to describe your poetry, I would call it surreal. But it could also be dark, violent, and bizarre. You had a way of taking everyday things and illuminating them with strangeness. But always there was that irrepressible humor of yours, even in your bleakest poems.

I confess that I don’t understand all your poems and that some work better for me than others. I think that’s true of all poets, even my favorite ones like you. Hey, we’re never going to please everyone. But the important thing is to keep on trying to take your poems to new places. And did you ever! Your poems defied classification. As one New York Times writer wrote of you, “Only a very foolhardy critic would say what any Simic poem is about.” So I’ll just mention a couple of my favorites.

I am so glad I finally got to hear you read at the University of Arizona Poetry Center, in 2018. It was a huge crowd and I was sitting way in the back. Your voice was not what it used to be, and I had difficulty hearing your words. As you read, you would often smile and wisecrack at many of your poems. Even when I couldn’t hear them I smiled and laughed with you.

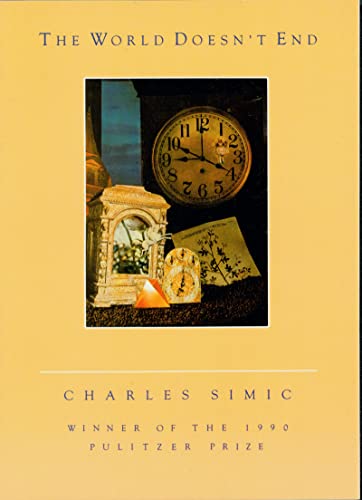

I just reread this untitled prose poem from your collection The World Doesn’t End, and I never grow tired of it. That first sentence cracks me up every time.

We were so poor I had to take the place of the

bait in the mousetrap. All alone in the cellar, I

could hear them pacing upstairs, tossing and turn-

ing in their beds. “These are dark and evil days,”

the mouse told me as he nibbled my ear. Years

passed. My mother wore a cat-fur collar which

she stroked until its sparks lit up the cellar.

I see you dedicated this book to Jim Tate. You were certainly kindred souls, though your styles were vastly different. And both of you fought the good fight in writing and publishing prose poetry, even when many insisted it’s just prose and not real poetry. Apparently those who chose this collection for the Pulitzer disagreed. That’s another thing I’d like to thank you for, in giving me the courage to write prose poems of my own and to challenge those who still seek to put limits on what a poem can or should be.

I’ll end here with this enigmatic micro poem which I think best reveals your indefinable style and character. Every time I wake up at three and look at my clock, I think of you. Thanks a lot!

THE VOICE AT 3:00 A.M.

Who put canned laughter

Into my crucifixion scene?

At first i wondered whether the mother in the cat-fur collar was the mouse’s mother or the writer’s mother. Then I realized that the lack of quotes on the last sentence made it the writer’s mother. But I wish it were the mouse’s mother, that would be more fun.

Rita